One of Scotland’s foremost educators and campaigners for computing science in schools has heralded the achievements of girls in the subject – but has sounded a warning about its future in classrooms.

Toni Scullion, founder of dressCode, a charity committed to closing the gender gap in computing science in Scotland, is concerned that falling numbers of computing science teachers coming into the profession risks undermining efforts to promote the subject to girls.

Ahead of International Women’s Day tomorrow, Scullion, who has formed a national network of computing science teachers, said Scotland urgently needs to address pupil equity in general if we are to carry on encouraging young girls to take the early steps on a career in tech.

She said: “I think the message for me is one of hope – because I do think it will happen, in terms of getting more girls into tech, but also of urgency – because the problem is not fixed.

“I do think more girls are going to start to pick it as a subject, but my worry is that the subject isn’t going to survive.

“I know that sounds really terrible, but if we’re going the way we’re going with the rate of the number of teachers coming in, that’s obviously going to have an impact on the uptake and access to the subject for pupils. So it might be that we get all these people who want to take it but it’s just not going to be there. We need to save the subject and make sure that the opportunity is there for all schools to nurture that talent coming through, because if it’s not there we’re going to miss a big wave that’s coming.”

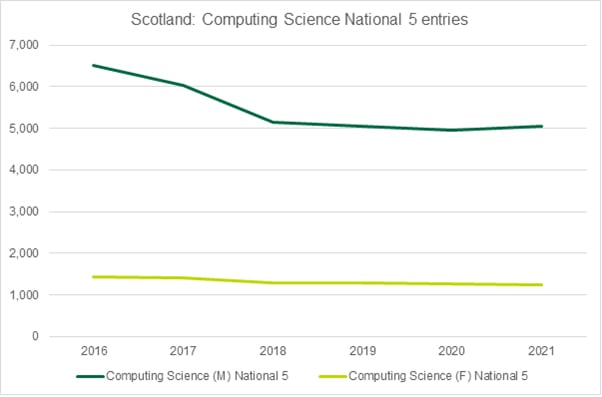

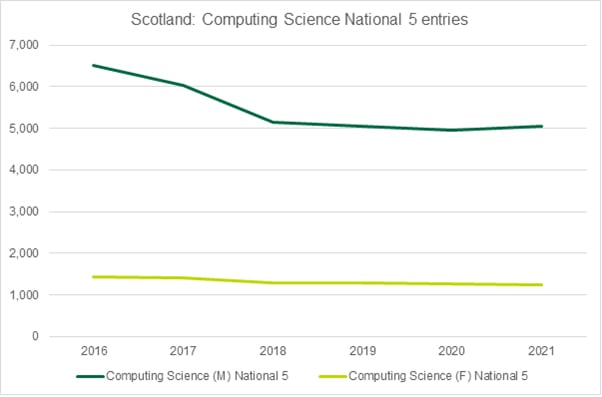

There is a systemic challenge to address. Over five years, between 2016 and 2021, the entries for National 5 qualifications at secondary school level in Scotland have shown a drop of over 20% participation, according to figures compiled by the British Computer Society. At Higher level, the ratio between males and female pupils was 6:1, highlighting a significant gap in gender equality for the subject. Recent statistics also show a flatlining number of Scottish-domiciled girls applying to do a computing degree, compared to an increase for boys.

Scullion, who has taught computing science at St Kentigern’s Academy in Blackburn, West Lothian, has led the charge to both prevent the looming cliff-edge of more computing science teachers leaving the profession than joining, whilst simultaneously addressing the gender gap.

She said: “It’s a hard problem and I think it’s just a series of things that have happened, where we have maybe taken our eye off the ball. And it’s not easy to fix one part of the problem, we need all the cogs to spin. Teachers and recruitment are the two big ones, and they’re properly knotted together, but I still think it’s all really solvable. And if you can address that, then I think you can get equity of access, which then leads to more pupils picking it as a subject.

She adds: “But even then, it’s not as easy as that because we need to start at the bottom and nurture that talent all the way up, so get them at nursery, get them really engaged at primary, continue to engage them in S1, S2 and just because the girls pick it at S3, it doesn’t mean you stop there. You need to nurture them at every stage and every age of the full pipeline – from nursery to CEO-level and back again. It’s got to be a virtual circle, so we’re not only providing opportunities for girls to do the subject but we’re reinforcing that with role models who can come back into the classroom and just complete that cycle.”

Scullion said there are lots of organisations, like her own, doing that work but she would like to see more joined up ‘strategic’ cooperation, to ensure that there is proper coordination of all efforts to close the gender gap in computing science.

When it comes to role models, she doesn’t just mean famous or well-known women in tech, who can be included in classroom resources to inspire girls to become coders or programmers. She’s also talking about peer mentors within schools, who are “more powerful” exemplars of what can be achieved at a local – and arguably more realistic – level.

“It’s those role models I think can make a huge difference,” she adds. “We know that kids are writing off or deciding whether or not they want to do tech at a young age. I think primaries are doing a great job, but we also need to support them, because they’re teaching every subject but barriers to access is one of the biggest things we need to overcome.”

However she cited the work of “real trailblazers” like Mari-Clare Mitchell of Mearns Primary in East Renfrewshire, who has a dressCode club and is encouraging girls to enter tech competitions and even speak at conferences. Scullion says teachers like Mitchell and others who are doing fantastic things need to be celebrated and “put on a pedestal” so other primaries might do the same.

“We know there’s lots happening out there but again it’s just trying to knit that together, and spread the word where we can,” Scullion says.

But she says it’s hard to maintain that enthusiasm when pupils get to secondary level. As it stands computing science is not a core subject from S1 to S3, meaning there’s a gap in provision. “It all falls apart a little bit because if they really enjoy it at S1 and then don’t get access at S2, then other things come on the radar,” says Scullion. “So, when they get to S3, they haven’t maybe picked it since S1, it’s just that much harder. If it’s dropped off at certain levels or you’re only getting it for one period a week, or if it’s not getting taught by an actual computing science teacher, because there are schools without that, it’s difficult.”

She adds: “‘When I say equity of access, it’s not that everybody needs to get a National 5 in computing science. It’s just about giving every single kid – boy and girl – the same opportunity to experience computer science in every single secondary school. And right now, that’s not happening.”

She said: “You don’t get the data on the number of girls picking it at S1 level, you just see it at National 5 level, but I think that’s got a big part to play. If we can get that right, I think other things will fall into place and have a bigger impact further up the school.”

To encourage more girls to get into the subject, Scullion has supported the development of the Hopper Awards for girls excelling in computing science, via her charity. They are named after Grace Hopper, a pioneering American computer scientist and mathematician who coined the term computer ‘bug’, which was named after a real-life insect – a moth – found in an early computer relay Hopper and her colleagues were working on, impeding its operation.

There is a now a Roll of Honour of Hopper Award achievers across Scotland, designed to encourage more girls to be inspired to take the subject. Other initiatives Scullion is working on include a lesson starter pack for teachers including a list of noteworthy women in technology, which has been put together by the Scottish Tech Army, a volunteer group. That resource will be shared through another group Scullion set up with fellow teacher Brendan McCart – the Scottish Teachers Advancing Computing Science (STACS) initiative, which was established as a professional learning, upskilling and development forum following the Scottish Technology Ecosystem review, authored by former Skyscanner executive Mark Logan.

Scullion has also engaged young people through the charity to send in pictures with inspiring quotes celebrating careers in computing science, which she then turns into posters. She’s currently working on a new website – Choose Computing Science – which is being built by Edinburgh digital agency TwoFifths Design using AI.

“We’re trying to get it launched as soon as we can. It’s looking really cool, and there’s a few bits to do but we want to use it to promote computing science, especially to parents and carers. There are lots of myths about computing science, and the language isn’t always that clear, so we want to use as many inspiring examples as we can to get that message across,” says Scullion.

She adds: “I do think it’s coming, though. There has been a kind of generational shift, I think, because there is now a much bigger tech sector than there ever has been before. Years ago you’d maybe hear that kids’ parents wanted them to go and be an admin assistant in an office, or something. But there is more awareness now, and parents are still big influencers. So this is basically influencing the influencers. We’re also not a general STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) site, we want it to be specific to computing science, but explaining in really simple terms what opportunities there are in Scotland.”

Scullion says the reason for the new website is to try and overcome what is still a “massive barrier” for all kids getting into tech, namely the mismatch between what the words ‘computing science’ mean, and what the actual job is.

“We have this really exciting, cool industry, but it doesn’t come across in the way we explain it,” she says. “It’s not like if you go on to a careers site for medicine, where the title kind gives you a hint of what it is. So what we wanted to do is not just put the job descriptions down, because I don’t think most young people would be able to guess what that means, let alone click on it. We just thought there’s no point doing that, and so we tried to create a really easy overview in a fun way, to make it as accessible and exciting as we can.”

The launch will be supported by postcards teachers can hand out to parents, just as another way of reaching that audience, as well as the posters that Scullion has designed to support the movement more widely. She is acutely aware that she needs to be able to reach parents on the channels they use. “We know that teachers are on Twitter [X], professionals use LinkedIn, parents are on Facebook, and kids are on TikTok, we need to reach the Scottish parents forum and homeschoolers as well,” she says.

She adds: “And we hope that the hashtag ‘Choose Computing Science’ can also appeal to industry, because they will realise that kids choosing the subject will benefit them, too.”

For International Women’s Day itself, Scullion feels “inspired” by all the young girls doing tech at school, and it’s those stories she wants to gather up and promote nationwide to show other girls that computing science can be a subject for them. Again, the Hopper Awards she has set up provides those role models, but she’s currently piloting a new approach with some 30 schools where she intends to be a bit more strategic. That means joining up the awards with the dressCode clubs, hackathons, industry speakers at assemblies, and hopefully even work placements.

“I’m hoping to do this for a year with the hunch that a targeted approach at every stage and every year will be where we hopefully see that gap narrowing not just in one year group, but in multiple year groups,” she says. “And then we can maybe use that data to parachute people in in a really strategic way. Again, that’s not being done, so we’re going to try and do that, just to see if we can move the dial a bit in the right direction.”