An international team of researchers based in Glasgow has developed a new manipulation method based on light that could one day be used to mass produce electronic components for smartphones, computers and other devices.

A cheaper and faster way to produce these components could make it less expensive to connect everyday objects – from clothing to household appliances – to the Internet, advancing the concept of the Internet of Things. The micromanipulation technique might also be used to create a safer and faster-charging replacement for mobile device batteries.

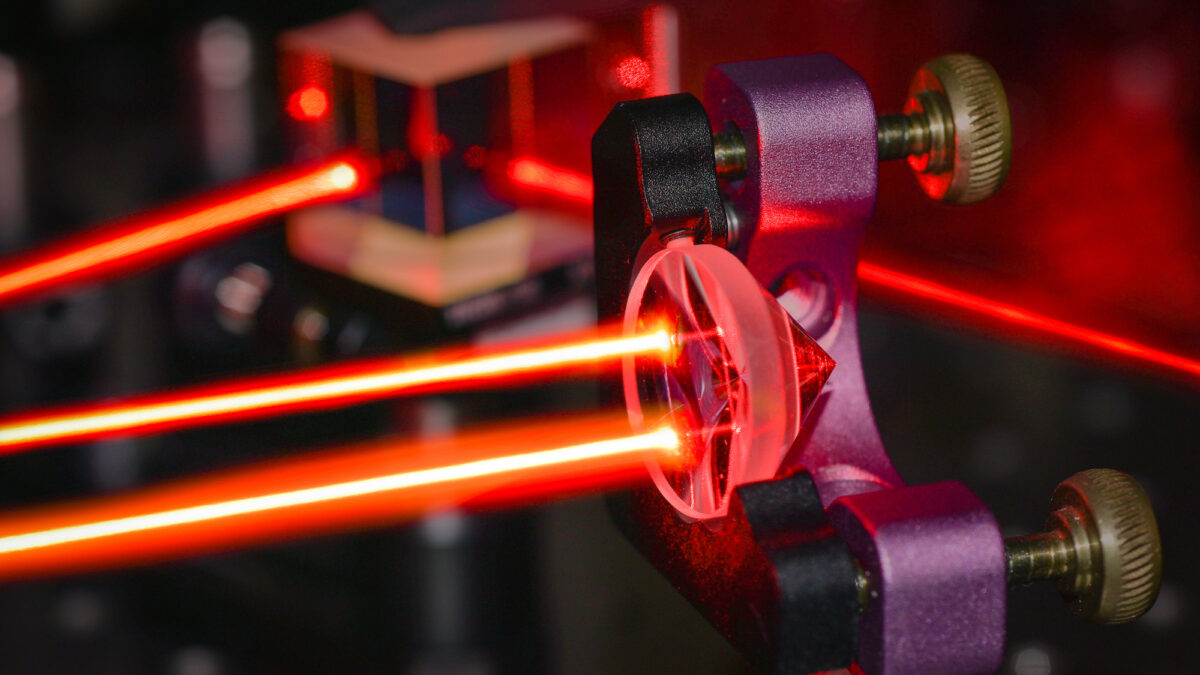

Optical traps, which use light to hold and move small objects in liquid, are a promising non-contact method for assembling electronic and optical devices. However, when using these traps for manufacturing applications, the liquid must be removed, a process that tends to displace any pattern or structure that has been formed using an optical trap.

In The Optical Society (OSA) journal Optics Express, researchers in Steven Neale’s Micromanipulation Research Group at Glasgow University, detail their method for using an advanced optical trapping approach known as optoelectronic tweezers to assemble electrical contacts. Thanks to an innovative freeze-drying method developed by Shuailong Zhang, a member of Neale’s research group, the liquid could be removed without disturbing the assembled components.

“The forces formed by these optoelectronic tweezers have been compared to Star-Trek like tractor beams that can move objects through a medium with nothing touching them,” said Neale. “This conjures up images of assembly lines with no robotic arms. Instead, discrete components assemble themselves almost magically as they are guided by the patterns of light.”

The researchers demonstrated the technique by assembling a pattern of tiny solder beads with an optoelectronic trap, removing the liquid, and then heating the pattern to fuse the beads together, forming electrical connections. They used the solder beads to demonstrate that in the future, these microparticles could be assembled and fused to create electrical connections.

“Optoelectronic tweezers are cost-effective and allow parallel micromanipulation of particles,” said Zhang, who is now at the University of Toronto in Canada. “In principle, we can move 10,000 beads at the same time. Combining this with our freeze-drying approach creates a very inexpensive platform that is suitable for use in mass production.”

The new technique could offer an alternative way to make the circuit boards that connect the components found in most of today’s electronics.

These types of devices are currently made using automated machines that pick up tiny parts, place them onto the circuit board and solder them into place. This process requires an expensive motorized stage to position the board and a costly high-precision robotic arm to pick up and place the tiny parts onto the device. The cost of these micromanipulation systems continues to rise as the shrinking size of electronics increases precision requirements.

“The optoelectronic tweezers and freeze-drying technique can be used to not only assemble solder beads, but also to assemble a broad range of objects such as semiconductor nanowires, carbon nanotubes, microlasers and microLEDs,” said Zhang. “Eventually, we want to use this tool to assemble electronic components such as capacitors and resistors as well as photonic devices, such as lasers and LEDs, together in a device or system.”

The researchers are now working to turn their laboratory-based system into one that would combine the optoelectronic tweezer and freeze-drying process in a single unit. They are also developing a software interface to control the generation of a light pattern based on the number of particles that needed to be trapped.

“We are now using a computer to generate the light pattern to move the beads, but we are working on an app that would allow a tablet or smart phone to be used instead,” said Zhang. “This could allow someone to sit away from the system and use their finger to control the movements of the particles, for example.”

Neale recently received funding to continue this line of research by using the new optical micromanipulation approach to create high energy density capacitors to replace batteries in mobile devices.

See also pureLifi breakthrough.