The world of education is currently undergoing a transformation. Schools – buffeted by the cruel winds of covid – have responded by moving into the digital space and, despite some bumps in the road, a new teaching and learning model is slowly beginning to emerge.

In this brave new world, textbooks and teach to the test looks increasingly anachronistic. Local authorities are replacing jotters with tablet devices and teachers are spending more of their development time brushing up on their own digital skills. The paradigm shift is further enabled by recent political decisions to inject fresh life into the national exams and education bodies, which could see, in the fullness of time, a move to more digitally-enabled – and continuous – assessment.

It may be a little too early to determine what exactly will come out of the other end but the Scottish Government has pledged to implement all 12 of the recommendations contained in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s recent report into Scotland’s ‘curriculum for excellence’, the national framework of education for children aged three to 18. Although broad-based, including a call for a greater focus on the role of knowledge in CfE, the role of technology in shaping children’s futures looks assured.

For Helen Donaldson, headteacher at Cramond primary school in Edinburgh, Covid-19 has merely accelerated a tech-focused pedagogical approach. Already a champion of iPads as a means of opening kids’ eyes to the possibilities of creativity and collaboration, Donaldson has expanded their use hugely through the pandemic and the results over the last 16 months – compared to the seven years prior, when their use was more limited – have been “stratospheric”.

“It is quite astounding the accelerated rate of change and the real transformation that we have managed to achieve,” she says. “So we had iPads around before, dabbled, and had people who really took them on. But I wouldn’t have said it would have had as big an impact on learning and teaching as I would have liked. There’s been a real pedagogical shift which in education we haven’t seen before.”

Donaldson recalls how at the onset of the first lockdown in March 2020 it felt a little bit like an “Apollo 13 moment” – shorthand for innovating in a hurry. Her first priority was the wellbeing of her staff and pupils alike, but the immediate move to home schooling presented a considerable challenge. At that point, the primary seven age group all had iPads on a one-to-one basis, but other year groups were not as well catered for. Donaldson – whose school is an affluent part of the city and does not attract much pupil equity funding – had to find budget to purchase more devices to improve the ratios across the school.

Online learning journals served as a stopgap to bridge the communications divide, with kids inevitably using parents’ devices at home. The use of Teams and Zoom as meeting platforms also rose, but Donaldson was not minded to go down the route of some private schools, after she had heard that many had switched to live learning on day one of the pandemic. Although many parents expected that rigour, with timetabled 9am till 3pm live online tuition, that’s “not good learning”, she explains. Her focus was on giving her staff the space to learn this new world themselves before going completely digital. “We had a teacher development day on Thursdays, and I told the parents to expect no communication from us that day, as staff needed to learn a new skill. They were building the spaceship as they were flying it.”

By October, primary five and six pupils were also issued iPads, and kids were largely back in school anyway. Cramond was by then in a position to do live learning and when the second lockdown came, the difference was “night and day”. “When second lockdown hit we were ready to move on to the next lane and go totally digital,” she explains. “We had the momentum and we weren’t reverting back.”

Despite the improvements, for Donaldson the tech opportunity is much wider. She no longer views the school as a physical building. To illustrate, she says that the barrier to some children’s learning has often been the school itself. iPads have given those kids a fresh opportunity to succeed, to access learning in a way that suits them.

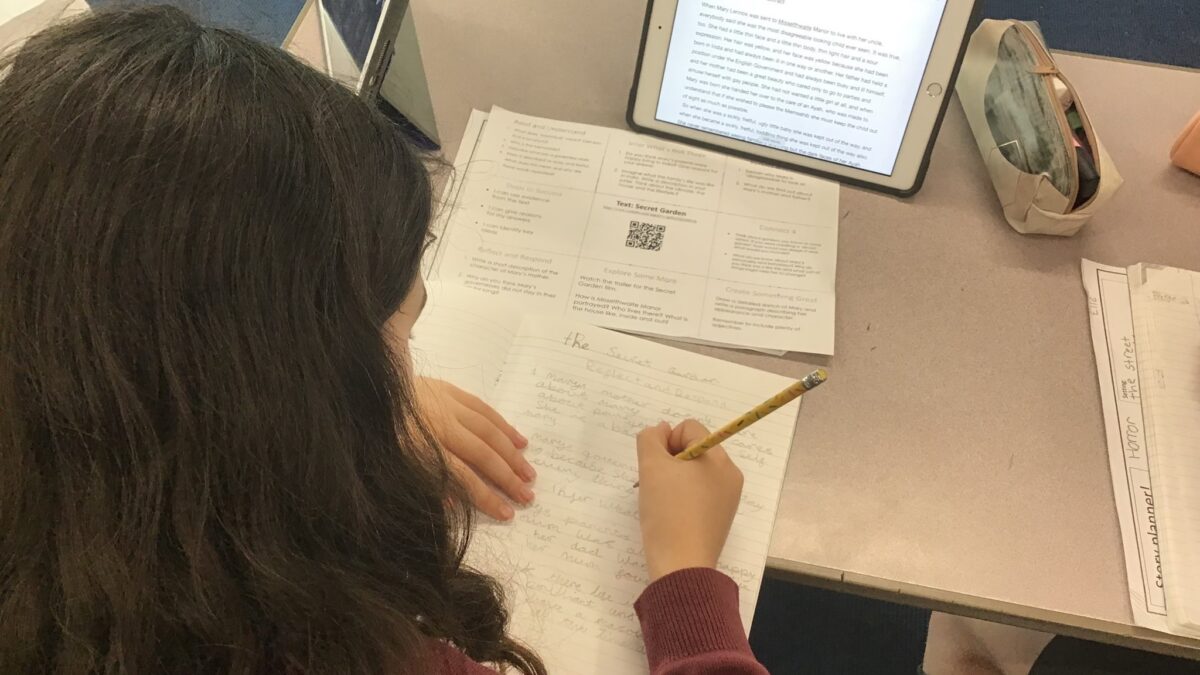

She is also an adherent to the principle of ‘flipped learning’, which is where students are given the chance to acquire the knowledge before they come to class, when they then discuss and apply what they’ve learned. In effect, the iPad has become the “teacher in the pocket”, whether children use it to communicate directly with their teacher, look something up online or use a myriad of creative features. She adds: “It’s blowing the lid off learning and empowering young people of all ages – from a three-year-old to an 18 year-old – it’s giving our children the chance to be who they need to be.”

The efforts of Cramond primary school are not happening in isolation. The school is one of many supported by Edinburgh City Council, which has committed £17.6m to ensuring every pupil from P6 to S6 across the capital will receive their own digital device. The 1:1 rollout starts in September and by the end of 2022 new iPads will have been issued to 27,000 pupils and staff, supplemented by 12,000 ’refreshed’ devices. In addition, iPads will be issued to P1 to P5 year groups on an ‘agreed ratio’. That approach has been mirrored in other parts of Scotland including in the Borders, Glasgow and Falkirk. Much of that work had been going on before the arrival of Covid and – at a corporate level – senior Apple education executives regard Scotland as ‘leading the way in thinking, experimentation, practice and delivery’.

What that means in practice on an iPad is in part down to the intuitiveness of the Apple design credo, long renowned for its accessibility features and ease of use. In a learning context, the tech giant has invested significantly in its creativity and coding capabilities, which reflect the company’s core strengths. The company shrewdly avoids trying to ‘replace teachers’, or become an online school, similar to the Khan Academy in the US.

Instead, it produced videos to help teachers get up and running with remote learning at the beginning of the pandemic and hired professional learning specialists to provide direct support into schools. As it currently stands, the company doesn’t see a role for itself other than as an ‘enabler’ of good learning. It is also not going down the data route unlike other tech companies whose business models depend on commoditising the end user, which will be reassuring to parents concerned over the privacy and security aspects of online learning.

When it comes to bringing learning to life, Donaldson says a poor lesson will not be improved by an iPad but the teachers in her school who have embraced the devices are now starting to “move mountains”. The creative and collaboration oriented features of iPads are also having a transformational effect. But will that mean kids eventually giving up using their jotters altogether?

Donaldson thinks not. She describes how youngsters when asked to express their feelings about the transition to high school via an animation, they set about it by hand drawing puppets, cutting them out, sticking them on a pencil and filming them, to the Ghostbusters theme tune. It was a blend of the physical and virtual worlds, she says, underlining how at ease kids are with using both.

“For them, technology is just there,” she says. “They don’t think ‘am I using technology or paper?’, they just merge. I love the iPad vision for learning, the simplicity, I love how joined up it is.

“The whole vision for learning absolutely chimes with where we need to go with learning in the 21st century. For me it’s always been about creativity, connection and collaboration.”

She adds: “It’s a really exciting time and if the only thing we look back on and say what changed in education as a result of the pandemic is that we got iPads then we’ve really missed a trick.”