A huge cloud of data is generating a 3D world of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

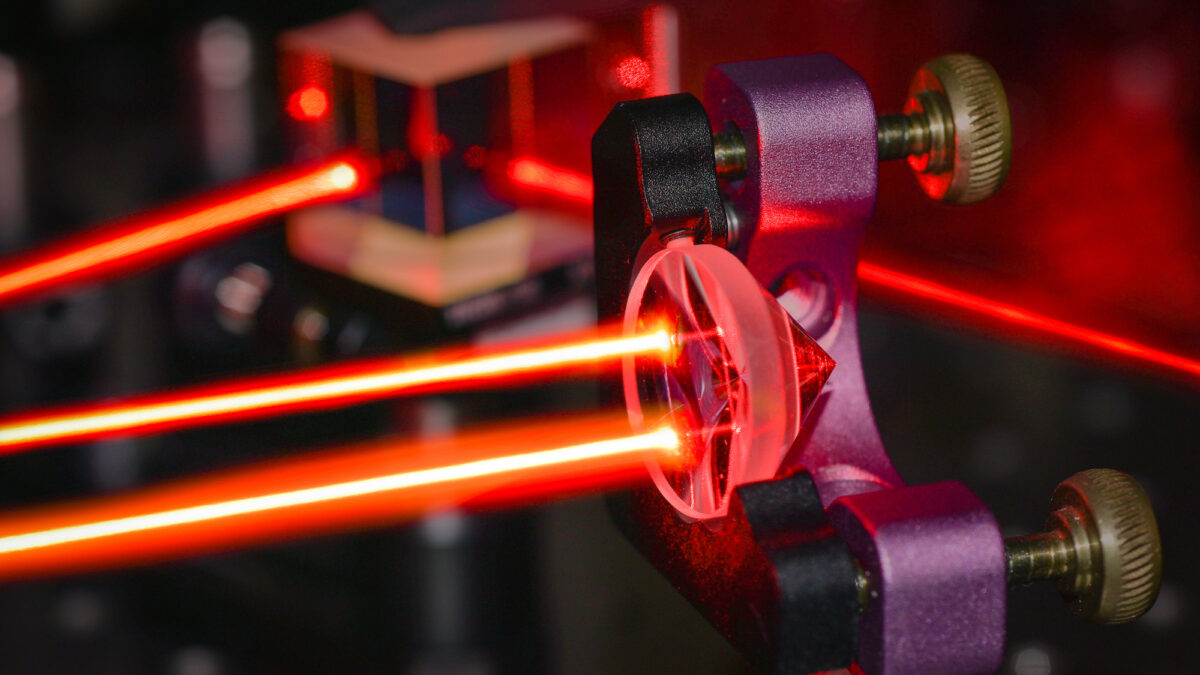

On the morning of Saturday 24 May 2014, as firemen watched over the smouldering remains of The Mackintosh Building, a team of data documentation experts from the Glasgow School of Art and Historic Environment Scotland stepped inside and set up powerful laser scanning equipment. The spinning head fired a laser one million times a second, through 360 degrees, and by recording the angle and the time taken for the light to return identified enough coordinates to generate a three-dimensional recreation of the building.

Fortuitously, the team had scanned the building’s exterior four years previously, allowing them to provide a rapid and accurate comparison post-fire. This proved invaluable in reassuring the city’s building control department that the western façade, which had borne the brunt of the blaze as it spread from the basement – where a projector ignited solvent in a student’s work – up through vents to the iconic library, was safe from collapse.

Just a few heavy stones at the top had moved, by about 4cm, and they could be numbered, removed and later reinstated. Another crucial contribution came in team’s ability to measure the amount of debris – 46 cubic metres – on the library floor. Structural engineers could confirm that the floor was also not in danger of collapse, allowing a forensic excavation of the material to go ahead. Sadly, very little of the library did survive – just 12 of the 10,000 books, which are being restored – but fragments of the structure are being analysed to inform the reconstruction.

The scanning of the interior over the past two years is not only assisting architects and the School of Art’s restoration team, but it also promises a ground-breaking record of the building’s life. A year later, over a period of two months, a full 3D laser survey of the entire interior of the building was undertaken. As areas changed, the team would re-scan – and by August this year it had a definitive version

– comprising 15 billion data point which, combined with a previous photographic survey by the Royal Commission and subsequent scans as the building is restored, will allow people to move around the building virtually and explore its history.

“We believe that it will be a really important and accessible record,” said Alastair Rawlinson, head of data acquisition at the School of Art’s School of Simulation and Visualisation (SimVis). “Something, that in 50 years’ time people will be able to use to look back at how the building changed over time, the extent of the damage it experienced in the fire and how it was subsequently restored as close as possible to Mackintosh’s original vision, all in a virtual 3D environment.”

‘SimVis has established an international reputation for its visualisation of the world’s heritage sites and the human anatomy, and in sound production and the use of 3D technologies in learning. Previously known as the Digital design Studio, it will formally launch as the School of Simulation and Visualisation next year, making it the fourth school at The Glasgow School of Art.

It is thought that work on the main structural envelope of The Mackintosh Building, including all external stonework, walls and roofs will be complete by July next year. Work on the interior is scheduled to begin in February and be finished towards the end of 2018, when contractors, the School of Art and independent conservators will commission and install specialist items. The building is expected to reopen by Easter 2019.

Why Mackintosh was ahead of Google

Restoration of the Glasgow School of art’s historic mackintosh Building, devastated by fire in 2014, began last month and the project’s leader has spoken about how the architect’s masterwork was an early example of a space that encouraged creativity through social interaction. “He’s known as one of the first modern architects,” said Liz Davidson. “The more you look at what he did here – the cleverness throughout the building and the future-proofing he put in and the way he used seating as social spaces; that’s what you find in a Google headquarters now. He built little social spaces all over.”

During a tour of the site for journalists Davidson, the senior project manager, added: “it was so ahead of its time. We think that to go back to mackintosh’s vision is actually giving us back a really modern building which has kind of been cluttered up over the last 100 years.” For example, mackintosh furniture had been replaced over time and wooden and brass features painted over. Under the project’s plans, the interior of the restored building will be much closer to the original than recent generations of students and art lovers have known.

But before mackintosh’s vision of a creative space can be restored, major structural work is required. Specialists have begun the process of removing the massive stone piers between the iconic windows on the west wall of the building, so that they can be inspected and where possible reinstated. Research to source authentic replacement timber is underway and specialists have begun the painstaking job of re-assembling 600-plus fragments of the original innovative electric lights retrieved following the fire.

“it’s taken a year of work by the restoration team, with our colleagues from archives and Collections, to develop our conservation methodology and sort the fragments into light ‘kits’,” said Sarah mackinnon, project manager. The kits are now being transformed – into 29 completely original lights and at least a further seven, partially using original glass fragments and brass parts – by specialist lantern maker lonsdale and Dutch in edinburgh. But, when “the mack” reopens in 2019, there will be

some modern touches not available to mackintosh; the lamps will be fitted with leD lights and the building will have underfloor heating and WiFi.

Privacy Overview

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.