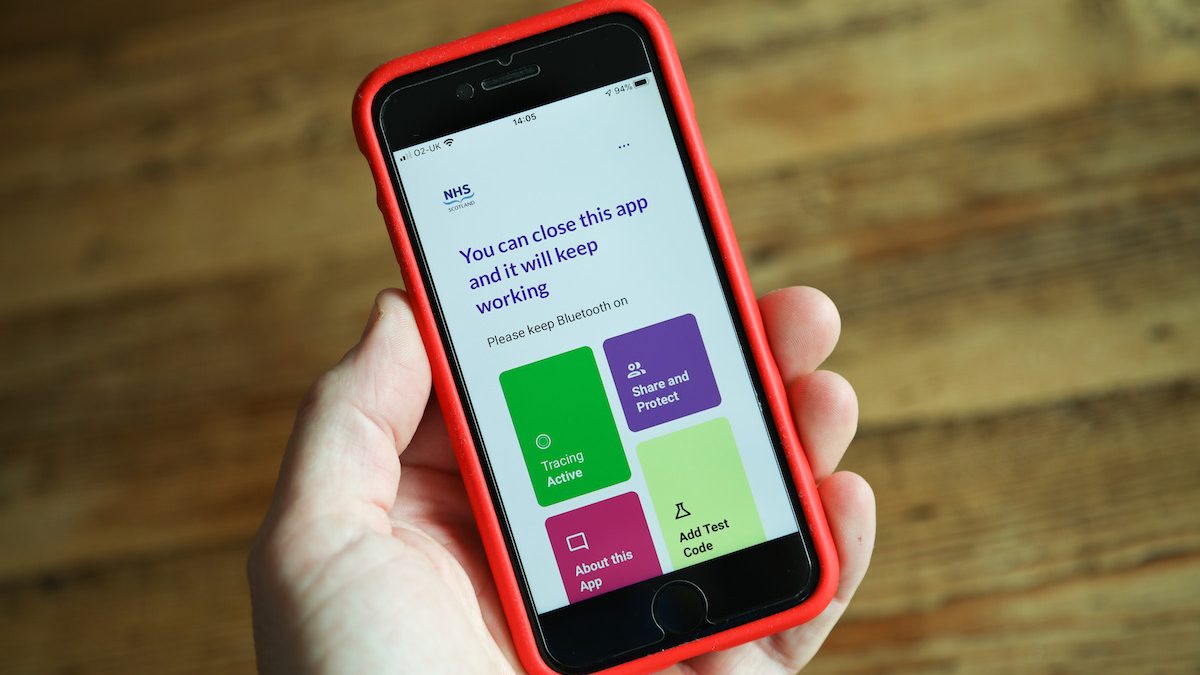

A new ‘proximity tracing app’ which alerts users when they come into contact with someone who has tested positive for COVID-19 is set to be released later this month by the Scottish Government.

Protect Scotland will be based on joint Apple and Google technology that has been in use in Ireland in the development of its Covid Tracker app, which has seen 1.5m downloads, equivalent to a quarter of the population, since its launch on July 7.

The Bluetooth-enabled technology, developed by software company NearForm, based in Waterford in the south east of the country, on behalf of the Irish Health Services Executive (HSE), is being adapted for use in Scotland by NHS National Services Scotland (NSS).

The application – described by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon as a “significant enhancement” to the Scottish Government’s Test & Protect regime – uses an ‘exposure notifications system’, which facilitates contact tracing apps’ access to Bluetooth and allow phones running the operating systems to swap anonymous IDs.

In Ireland, the app works by using the Bluetooth signal on an Android or iPhone to exchange a digital “handshake” with another device also running the Covid Tracker app when users come within two metres of each other for longer than 15 minutes. The anonymous keys are stored in a log on the phone, which the HSE may ask users to upload if they receive a positive diagnosis for Covid-19. That log can then be used to track unnamed contacts, with an alert delivered to affected people through the app.

The software was built on decentralised technology, which proved to be a major stumbling block for Apple and Google working with the NHS in England earlier this year, after the tech companies refused to progress with a centralised database approach, whereby the NHS would have direct access to sensitive users’ data.

The UK Government has since abandoned that approach – for a number of reasons including privacy – and is now also working on a decentralised platform based on the Apple-Google model, with trials taking place on the Isle of Wight and in London as of mid-August. An exact date for the launch of the app by NHSX – the Department of Health’s digital arm – has not yet been announced. A version of Covid Tracker has also been made available to citizens in Northern Ireland and was the first part of the UK to use such a system.

Users who test positive for COVID-19 are a sent code by SMS, which can then be entered into the app. They are subsequently asked to share the random IDs their phone has been swapping with other app users over the previous 14 days. Once a user agrees, these ‘diagnosis keys’ allow the app to tell those people that they have been exposed to the virus.

The Scottish Government’s approach was revealed in its Programme for Government announcement this week, with Protect Scotland described as a system to complement existing methods used as part of a network of human contact tracers working under the Test & Protect programme. Around 60% of the population would be required to download the application in order for it to achieve maximum efficacy and suppress the pandemic, according to a consensus of expert opinion. That download rate has not been achieved by any country that is using similar contact tracing app technology.

The Apple-Google system – called the Google Apple Exposure Notification (GAEN) system – is set to be enhanced over the coming weeks with the addition of an ‘exposure notification express (ENE)’ system, which does not require public health service approved apps to be downloaded by users.

This means anyone who updates to new iOS and Android software and has ENE enabled will be able to be sent notifications by public health authorities, allowing those who do not have the app installed to be notified that they may have been exposed to someone who has tested positive for the virus. This should increase the availability of contact tracing through smartphones among people unwilling or able to download apps. Apple released a 12-step process of how this will work in a recent blog post.

NearForm in Ireland is regarded as one of the country’s leading software companies and specialises in bringing cloud computing to large enterprises and counts The New York Times, Intel, IBM and Microsoft among its customers. Although based in a town more famed for its glassware than its software, it has built a distributed workforce with 90 per cent of its staff working remotely before the pandemic.